Review

Overview

Teaching: 15 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

What are Data, Data Types, Data Formats & Structures?

Objectives

Review introductory data concepts.

Prerequisite

This curriculum builds upon a basic understanding of data. If you are unfamiliar with basic data concepts or need a refresher, we recommend engaging with any of the following material before beginning this curriculum:

- Data 101 Toolkit by the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh and the Western Pennsylvania Regional Data Center

- Data Equity for Mainstreet by the California State Library and the Washington State Office of Privacy

- Open Data 101: Breaking Down What You Need to Know by GovLoop and Socrata

- Introduction to Metadata and Metadata Standards by Lynn Yarmey

Working Definitions

Below are key terms and definitions that we will use throughout this curriculum:

Data: For the purpose of this curriculum, data are various types of digital objects playing the role of evidence.

|

|---|

| Schutt, R., & O’Neil, Cathy. (2014). Doing data science. Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly Media |

FAIR Data: An emerging shorthand description for open research data - that is applicable to any sector - is the concept of F.A.I.R. FAIR data should be Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable. This is a helpful reminder for the steps needed to make data truly accessible over the long term.

Data curation: Data curation is the active and ongoing management of data throughout a lifecycle of use, including its reuse in unanticipated contexts. This definition emphasizes that curation is not one narrow set of activities, but is an ongoing process that takes into account both material aspects of data, as well as the surrounding community of users that employ different practices while interacting with data and information infrastructures.

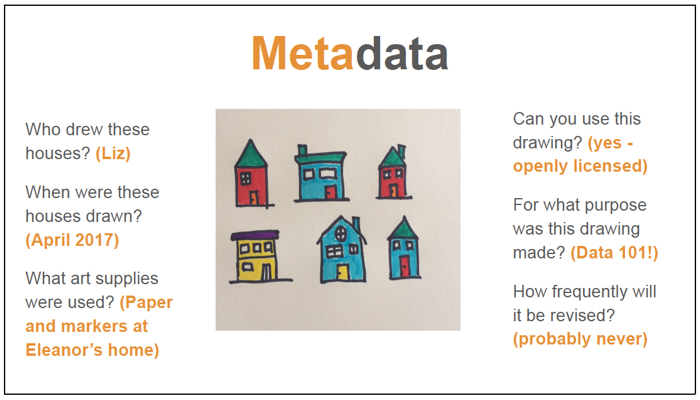

Metadata: Metadata is contextual information about data (you will often hear it referred to as “data about data”). Metadata, at an abstract level, has some features which are helpful for unpacking and making sense of the ways that descriptive, technical, and administrative information become useful for a digital object playing the role of evidence. When creating metadata for a digital object, Lynn Yarmey suggests asking yourself “What would someone unfamiliar with your data (and possibly your research) need in order to find, evaluate, understand, and reuse [your data]?”

|

|---|

| Slide from Data 101 Toolkit by the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh and the Western Pennsylvania Regional Data Center CC-BY 4.0 |

Structured Metadata Is quite literally a structure of attribute and value pairs that are defined by a scheme. Most often, structured metadata is encoded in a machine readable format like XML or JSON. Crucially, structured metadata is compliant with and adheres to a standard that has defined attributes - such as Dublin Core, Ecological Metadata Language or EML, DDI.

Structured metadata is, typically, differentiated by its documentation role.

- Descriptive Metadata: Tells us about objects, their creation, and the context in which they were created (e.g. Title, Author, Date)

- Technical Metadata: Tells us about the context of the data collection (e.g. the Instrument, Computer, Algorithm, or some other tool that was used in the processing or collection of the data)

- Administrative Metadata: Tells us about the management of that data (e.g. Rights statements, Licenses, Copyrights, Institutions charged with preservation, etc.)

Unstructured Metadata is meant to provide contextual information that is Human Readable. Unstructured metadata often takes the form of contextual information that records and makes clear how data were generated, how data were coded by creators, and relevant concerns that should be acknowledged in reusing these digital objects. Unstructured metadata includes things like codebooks, readme files, or even an informal data dictionary.

A further important distinction we make about metadata is that it can be applied to both individual items, or collections or groups of related items. We refer to this as a distinction between Item and Collection level metadata.

Metadata Schemas define attributes (e.g. what do you mean by “creator” in ecology?); Suggests controls of values (e.g. dates = MM-DD-YYYY); Defines requirements for being “well-formed” (e.g. what fields are required for an implementation of the standard); and, Provide example use cases that are satisfied by the standard.

Expressivity vs Tractability All knowledge organization activities are a tradeoff between how expressive we make information, and how tractable it is to manage that information. The more expressive we make our metadata, the less tractable it is in terms of generating, managing, and computing for reuse. Inversely, if we optimize our documentation for tractability we sacrifice some of the power in expressing information about attributes that define class membership. The challenge of all knowledge representation and organization activities - including metadata and documentation for data curation - is balancing expressivity and tractability.

Normalization literally means making data conform to a normal schema. Practically, normalization includes the activities needed for transforming data structures, organizing variables (columns) and observations (rows), and editing data values so that they are consistent, interpretable, and match best practices in a field.

Data Quality From the ISO 8000 definition we assume data quality are “…the degree to which a set of characteristics of data fulfills stated requirements.” In simpler terms data quality is the degree to which a set of data or metadata are fit for use. Examples of data quality characteristics include completeness, validity, accuracy, consistency, availability and timeliness.

Data Type Data type is an attribute of the data. It signifies to the user or machine, how the data will be used. For example, if we have a tabular dataset with a column for Author, each of the cells within that column will be of the same data type: “string”. This tells the user or the machine that the field (or cell) contains characters and thus only certain actions can be performed on the data. A user will not be able to include a string in a mathematical calculation for example. Common data types are: Integer, Numeric, Datetime, Boolean, Factor, Float, String. Terminology can differ between software and programming languages.

Data Formats and Structures

Key Points

Definitions